My dad, Pete Mondale, was a lifelong teacher who spent most of his career as a professor of American Studies. His mother was a music teacher who taught for a while in a one-room schoolhouse. He went to public schools in the tiny farming town of Elmore, Minnesota, and thanks to the government-funded GI Bill, he was able to go to college. He later earned his doctorate at the University of Minnesota, a great public institution. He reached the pinnacle of his career in the 1960s when he founded the Department of American Studies at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa where he inspired a very special group of students. He also made a difference in the lives of students at George Washington University where he taught for many years. A number of them became family friends, and growing up, I saw how much they respected him. After he retired, his Alabama students invited him back for a celebration in his honor. They came from all over the country to tell him how he had changed their lives, a type of recognition that is rare in the life of a teacher.

My father was also a wonderful teacher to us, his seven kids. He introduced me to great American authors as a child. He and I laughed together over Mark Twain, and to impress him, I even tried to plow through all of Twain’s books at age 12. He also taught me valuable lessons about the art of teaching. He never gave us the answers when we kids were struggling with homework. Instead, he would lead us to discover our own answers by asking questions. This infuriated me at the time, but now, as a teacher myself, I recognize it as a gift.

I say all this to explain why education and particularly public education were so important to him, and thus, to me. He believed that public schools were the bedrock of our democracy, and often cited examples from history to prove how much Americans valued them. “Just look at the Northwest Ordinance,” he would say. When we were barely even a country, all the new states had to set aside land for public universities and “forever encourage schools.” Land grant colleges were another example he liked to pull out to show how dedicated Americans were to public education. (In 1862, the federal government gave states over 17 million acres of public lands to manage, with the proceeds going to support public universities.)

My dad would often talk about how his parents’ generation, the sons and daughters of poor immigrants, got their start in this country thanks to public schools. His father-in-law, my grandfather, came to America from Italy as a teenager, and talked about public schools as one of the greatest institutions this country had to offer.

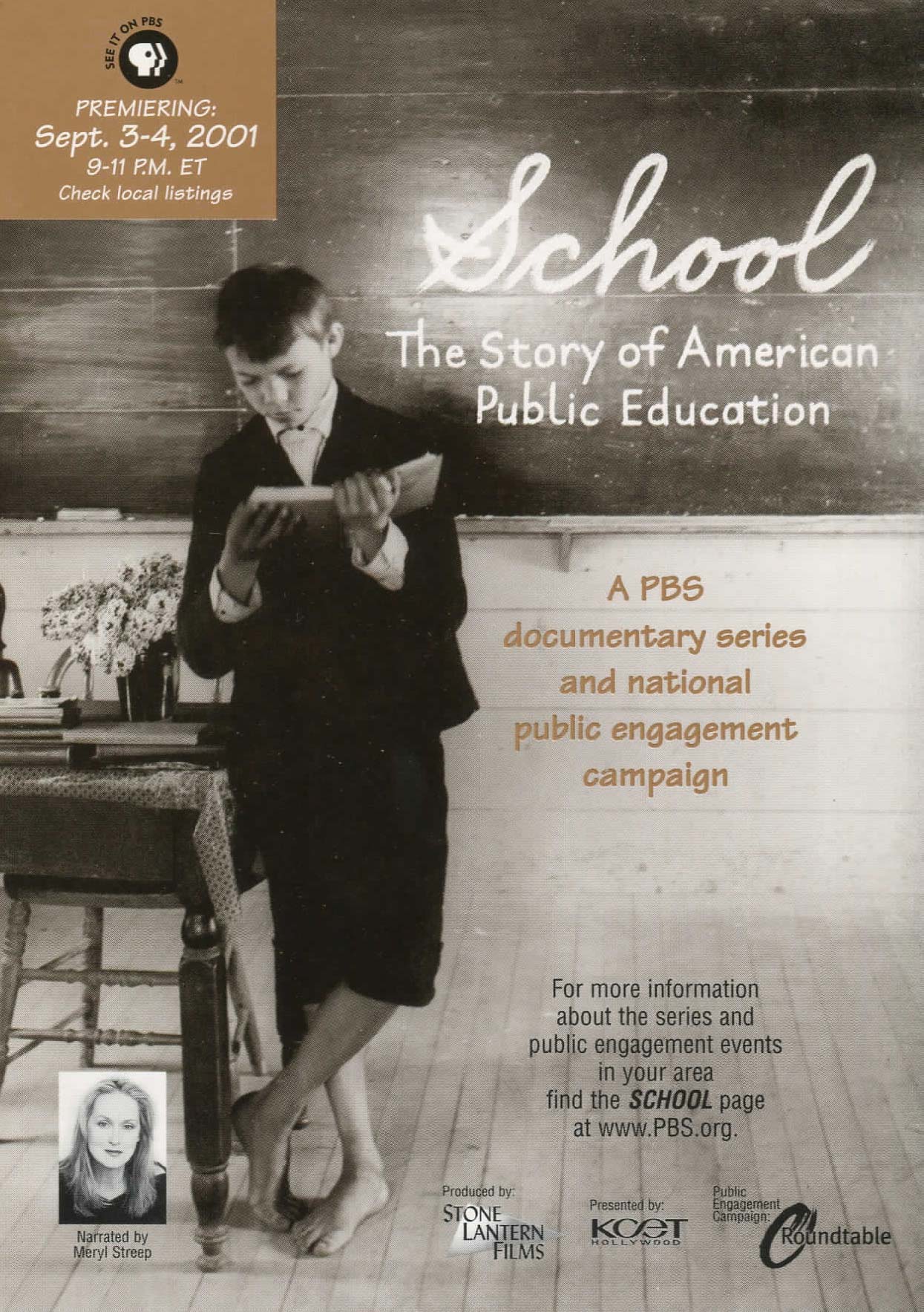

My mother, became a teacher of English to adult immigrants in the public schools of Washington, DC. I grew up hearing so much about public education at the dinner table, that in the 1990s, I decided to make a film series about it called SCHOOL. Ten years after the series aired, my father sent me a book by Diane Ravitch called The Death and Life of the Great American School System. “This is a great topic,” he said. “You’ve got to make a film about this.” I was a high school teacher at the time, but as we talked it over, I came to see that he was right.

What was happening to public schools as a result of the market-driven “reform” movement seemed truly alarming. Funded by corporate philanthropists including Bill Gates and the Waltons (owners of Walmart), a powerful coalition was essentially privatizing American public schools. Calling it “reform,” the private sector was taking control of public schools away from communities, elected officials and educators, harming the most vulnerable children. What galled my dad the most was that these “reformers” were making teachers and their unions the villains. He would shake his head and say, “I can’t believe they’re scapegoating TEACHERS of all people! That is just incredible…”

After doing some research with my collaborators, and watching films including Waiting for Superman that pushed “reformers’” message––U.S. public education is broken, bad teachers are the problem, and only the private sector can fix it––I became concerned by what I saw as a propaganda campaign. So I took a leave from teaching to start work on a new film called BACKPACK FULL OF CASH. Sometimes I got discouraged during the years of making the film, and my dad would pat me on the shoulder saying, “Don’t give up. You’ve got a great topic there.” Then in the spring of 2014 while filming in Philadelphia, I got the news that my father was dying. I wish he had been able to see the finished film with Matt Damon’s narration and an audience of educators, parents and supporters of public schools.

Now I wonder what he, a historian, would have thought about the election of Donald Trump. I’m sure of one thing––he would strongly oppose Trump’s views on public education, especially his reported plan to funnel billions in federal funds to privately-run charter schools and vouchers for religious schools. I know that my dad would have seen this as a threat to social justice and democracy, and he would have been right.

Sarah Mondale, Director – Backpack Full of Cash